A few weeks ago I wrote about the tenuous nature of genre. There’s an aspect of genre that I briefly mentioned that I think should be addressed more fully; that of the inherently political and racist nature of the concept.

Before that, a bit of personal background. Being a native of St. Louis, Missouri, I’m intimately familiar with the practice of asking someone you’re just meeting in the area “What high school did you go to?” On the surface, this is a perfectly innocuous question. However, in St. Louis, this question is actually carrying a heavy load. The city of St. Louis has a long history of poorly performing schools (at least by reputation) and a strong Catholic education system. As such, one cannot necessarily tell where someone went to school based on the neighborhood or suburb in which they grew up. The name and location of one’s high school is a shorthand for one’s socioeconomic level and cultural associations. The answer to the question provides the asker with a stereotypical assessment of the responder with which to judge them. This is likely not unique to St. Louis, MO, but it is the context in which I think about the political nature of musical genre. What music we listen to says a lot about where we come from and who we associate with.

In truth, one could argue that there are only two types of music: classical and folk. Classical music is that traditionally intended for the cultural elites (e.g. anything with an orchestra or its derivatives), and folk music is everything else for everyone else. To illustrate, Nina Simone referred to herself as a folk artist; not jazz or soul or however you’d find her filed in a record shop. Personally, I would argue that there are three types of music: classical, folk, and jazz. To me, jazz features elements of both classical and folk that create a third and separate thing. Jazz is usually art music implying it’s directed at cultural elites, but it is also visceral in a way that leans more folk than classical. Furthermore, it spent many years being a popular form of music for the masses, i.e. pop music. It is both, and therefore unique.

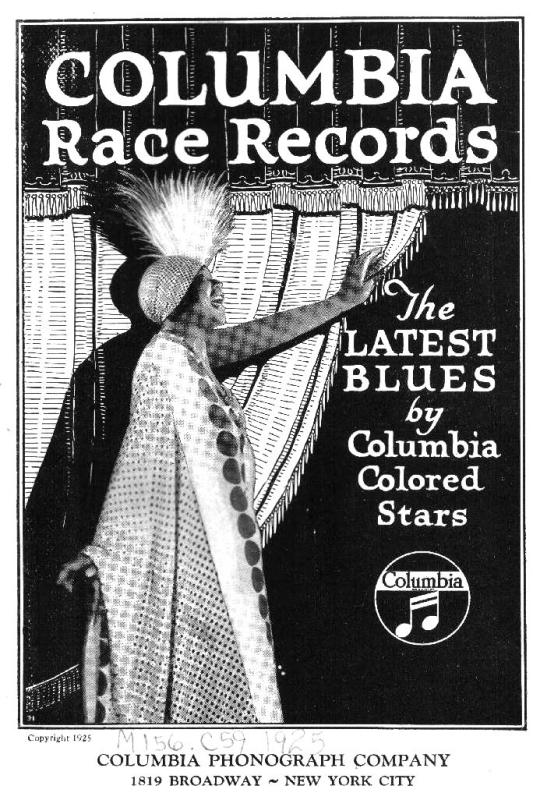

Much of what we think of as musical genre arose in the 20th century with the concept of “race music.” Not considered a derogatory term at the time, “race music” was the name for the phonograph recordings of black artists of the 1920s and before. These records featured black artists and were marketed to black consumers, only later beginning to draw white audiences. By the 1940s, BILLBOARD magazine was tracking sales of “race music,” eventually changing the name to Rhythm & Blues/R&B by the end of the decade.

As we know, a sea change occurred in music over the 1950s, and that sea change was called “Rock & Roll.” “Alan Freed’s use of the term rock-n-roll in the 1950s is often considered definitive. He used the term to refer to R&B combos, black vocal groups, saxophonists, black blues singers, and white artists playing in the authentic R&B style” (What distinguishes Rock-n-roll from Rhythm-n-Blues?). Rock & Roll was R&B performed by and marketed to white people. Elvis Presley, Bill Haley, and Jerry Lee Lewis were recording stylistically identical music as Ray Charles, Chuck Berry, and Little Richard, with the only significant difference being the color of the skin of the performers and the population to whom the music was marketed.

Remember. We’re talking about Jim Crow America. Racial segregation was paramount in the public realm. The record companies saw an opportunity to use black artists’ work and style and recast it for the fragile white people to make it safe for them. Elvis didn’t steal Rock & Roll from the black population, the executives did. Elvis was a dumb hick with good looks, raw talent, and genuine love for the music. Any of us would have taken the opportunity he had.

It’s from these early periods that we see a racial divide in music that persists to this day. In other words, the very idea of musical genre is racist in nature.

Leave a comment